Folks in Sheridan County, almost to the littlest urchin, know of Ernest Hemingway's various stays in the Big Horns. Yet another author important to both American history and American literature spent time in Johnson, Sheridan, and other Wyoming counties in the summer of 1866.

Ambrose Gwinnett Bierce lives on in the public consciousness from a handful of short stories, such as "Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" and"Chickamauga," and the satirical

Devil's Dictionary. Few know his other war stories and tales of supernatural horror. Even fewer have read his reams of journalism--spicy editorials, reviews and even a little muckraking (before objectivity overtook journalism as the preferred voice).

Before he was an author, Bierce was a farm boy, a bricklayer, military academy cadet, printer's devil, and volunteer soldier in the Civil War who lived almost four years warfare.

In the summer of 1866, Bierce took part in a military inspection of Forts Reno, Kearny, C.F. Smith, and Benton, accompanying General William B. Hazen's expedition as a civilian cartographer. What follows is not just the account of Bierce's time in the Big Horns but a snapshot of his tumultuous and colorful life.

|

Bierce's most iconic portrait, by John Herbert Evelyn Partington.

Bierce was noted for having a skull and cigar box

always on his desk. Click to enlarge. |

To introduce Bierce is no easy task. His many dimensions included compassion, dedication to the underdog, idealism, fierce opponent of nonsense, nonconformity, as well as verbal brutality, misanthropy, and cynicism. He was a person so ferociously ahead of his time that his contemporaries struggled to classify him...politely.

With satire as piercing as his gray eyes and fiery as his auburn locks, Bierce ruffled more than his fair share of feathers in his day. In the biography Bitter Bierce, author C. Hartley Grattan describes the writer as "a perfectionist at a time when public morals were low and private morals were nine tenths hypocrisy." Accordingly, 'Bitter Bierce', a.k.a. the 'wickedest man in San Francisco', called things as he saw them, brooked no nonsense, and cared not a whit whom he razed to ashes with his verbal conflagrations--as long as they deserved it.

One can trace the threads of Ambrose Bierce's nonconformity to his childhood. As childhoods in the mid 1800s went, his was rough but no rougher than many. In addition to losing three of his twelve siblings, his father, Marcus Aurelius Bierce, ruled the family with an iron hand. Marcus, well-read for his time and station, had a decent library, which laid the foundation for a love of learning in his most rebellious son. Such a dedication to improvement would only embolden the lad under his father's lash, as he later reflected, "Disobedience is the silver lining to the cloud of servitude."

Of Ambrose Bierce's family, his abolitionist uncle, Lucius Verus Bierce, had the most influence on the principled and angry young man. (Lucius was a militant abolitionist with connections to John Brown).

At age 15, Bierce left home, seeing no reason to stay in hicksville with his family of squares, "I was one of those poor devils born to work as a peasant in the fields, but I found no difficulty in getting out." He tried the Kentucky Military institute, but dropped out at age 18, then becoming a printer's devil for an abolitionist newspaper in Warsaw, Indiana, until the outbreak of the Civil War.

At just 19 years old, Ambrose Bierce answered President Lincoln's call for volunteers within a week of the Battle of Fort Sumter.

The next four years would shape Bierce's humor and place in the world in ways he probably never fully grasped. The horrors he experienced and witnessed made an indelible mark on his psyche, causing a mix of what would now be called PTSD and a strangely affectionate longing for the glory days.

Early skirmishes finished quick and with relatively few casualties, lulling men on both sides into thinking the war would be over soon. How tragically wrong they were. As the battlefield is wont to do, it pushed soldiers to absolute honesty about their own courage and conviction. The first major Battle in which Bierce fought, the Battle of Rich Mountain, brought out heroics in the young soldier. Amid a barrage of Confederate bullets, Bierce dragged a gravely wounded comrade to safety, winning renown and a promotion to sergeant major.

Bierce later found himself at Shiloh where his platoon was met with a bloody ambush. In Bierce's fashion, he later immortalized the tragedy and carnage vividly in the short story, "The Coup de Grace," telling not just of slaughter but gory details such as pigs feasting on soldiers' corpses and the wounded being burned alive in brush fires.

|

Bierce at age 21. Photo from the

Click to enlarge.

|

Shiloh wasn't the end of it. After Bierce found himself at the Siege of Corinth aiding in evacuations, as well as several more battles--providing reconnaissance at two, fighting Southern guerrillas, his luck thinned. At the Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, June 27, 1864, three days after his 22nd birthday, a Confederate sharpshooter's bullet struck him behind the left ear. Despite the initial appearance of death, Bierce miraculously survived only to be hauled on a jostling flatbed railcar for two days--almost three thousand minutes of skull-pounding agony--back to Warsaw. Union doctors were unable to remove all of the bullet; it caused Bierce migraines and blackouts the rest of his days.

Bierce's short short story, "The Other Lodgers," perhaps expresses his state of mind after being shot. The story blurs the lines between the living and the dead; biographer Roy Morris Jr. suggests Bierce, like so many near-death survivors, wasn't "convinced of his own survival." Case in point: the story's narrator, also suffering from a shot to the head, relates the story in a hazy fugue.

Beyond getting shot, 1864 proved a rough year for the future satirist. His engagement to Bernice Wright fizzled. Later in the year, Confederate troops captured Bierce after a breakneck chase through a corn field, despite Bierce spending the night in a tree. Luckily, his captors' hearts were just not in it, and he sneaked away in the night, dodging dogs and fences, avoiding Andersonville and a fate worse than death.

The following January, Bierce received the boon of a medical discharge. Having seen near constant combat for the better part of four years, he was ready for a respite. Despite his affectionate longing for what was perhaps the rush of war, those years haunted Bierce. Of the enthusiastic young soldier who entered the war, he later wrote "I am bound to answer that he is dead."

Along with migraines and blackouts, the spectre of death haunted Bierce. American literary critic Edmund Wilson, who perhaps is missing the point of Bierce's use of death, supposes it was "Ambroce Bierce's only real character." As a man who beheld as much pointless slaughter, Mr. Bierce was justifiably fixated upon and perhaps perplexed by death, which can be seen in stories such as "Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge" and "Chickamauga."

Amid the aftershock of the "grand holocaust of slaughter," Bierce's wicked sense of humor and orneriness emerged. As the war drew to a close, Bierce and some of his fellow soldiers decided to get even with a particularly annoying lieutenant. Lieutenant Haberton droned on about his exploits with women, arrogantly confident in his proclamations of rakishness. Bierce and his fellows convinced a young orderly, one whose effeminate features fit the task, to deck himself in full female regalia and stalk the pompous Haberton. Things went according to plan until Haberton began to ply his wares, a Confederate shell exploded in the floor above. This sent the young orderly fleeing from the room, screaming "Jumping Jee-rusalem," and ditching his "girl-gear." Vexed, Haberton sported "the sickliest grin that ever libeled all smiling," reportedly squeaking "You can't fool me!" It was amazing anyone heard the lieutenant's words above the explosive laughter.

After Bierce's medical discharge from the Union army, he went straight to work for the Treasury Department. His job was to track down and confiscate cotton bales, valued at $500 apiece--roughly $7500 in contemporary dollars. The enterprise proved a rough and dangerous one, a cat and mouse game not entirely unlike that of Treasury agents and mobsters in the Prohibition era.

Exacerbating Bierce's peril was his integrity. The war may have killed the young man in Bierce, but the youth's steadfastness remained: Ambrose Bierce proved the rare Treasury agent who could not be bought. Such an attribute pitted him against all and sundry who benefited from the crooked enterprise of selling cotton bales to the highest bidder, as well as war-weary and Union-hostile residents of the postbellum South--and former Confederate soldiers returned from the war who looked on Lee's surrender as an ephemeral formality.

In April of 1865, Bierce relocated to Selma, Alabama, a veritable hellhole of corruption, thievery, and somewhat justified malice toward the North. Prior to Bierce's arrival, a Union cavalry brigade, under the command of Major General James Wilson, burned down most of the town, including military targets, local businesses, some homes, and the shipyard. Adding insult to injury, Wilson's boys rounded up hundreds of horses and mules, shot them dead, and left them to rot in the Alabama sun.

Suffice to say, Bierce didn't much enjoy his time in Selma, finding as much scorn and hate sent his way as empathy with Selma's residents. Two marshals, found with their throats cut in the street, marked just the beginning of trouble in the area. The constant danger was such that Bierce and his superior, Captain Sherburne Eaton, would say something memorable to each other every night when they parted in case one was killed in the night.

Thankfully, Bierce's time in postbellum Alabama had a ceiling. He received a letter from General William Hazen, whom he had served as acting topographical officer from 1863-1864, summoning Bierce to join an inspection tour of forts in the Powder River Territory. Bierce jumped at the chance with nary a second thought.

William Babcock Hazen was one of the precious few people Bierce admired and trusted, writing once that Hazen was "the best hated man I know." The general's soldierly directness and outspoken disdain for political BS impressed the younger soldier--disdain, biographer Richard O'Connor suspects, served as the means by which Hazen could be diverted from providing his particular brand of uncensored commentary on Grant's, Sherman's, and Sheridan's postwar political campaigns. To put it bluntly, there were fears, probably, that Hazen had some dirt on the former-military-men-cum-politicians.

Hazen, formally appointed as inspector general of the Department of the Platte, was tasked with providing reports on the state of the Mountain District, which included Forts Reno and Phil Kearny in Wyoming and C.F. Smith and Benton in Montana.

Bierce joined the Hazen expedition as a civilian cartographer, later writing of his position that "I was not a pilgrim, but an engineer attaché to an expedition through Dakota and Montana, to inspect some new military posts. My duty, as I was given to understand it, was to amuse the general and other large game, make myself as comfortable as possible without too much discomfort to others, and when in an unknown country survey and map our route for the benefit of those who might come after." A cook and teamster, as well as occasional cavalry escorts and guides, rounded out the merry band. Hazen, Bierce, and company set out from Omaha in July of 1866.

The first of many grand sights Bierce beheld--to also include Crazy Woman Flats, Clear Fork, the Black Hills and the Tongue, Platte, Little Bighorn, and Yellowstone Rivers-- was Nebraska's Courthouse Rock, a popular landmark for westward settlers.

The unfolding journey made Bierce both apprehensive and, perhaps for the first time since the war, animated. One of the few highlights of Bierce's youth was reading about the adventures of Captain Mayne Reid, who explored "Indian Country." Of Courthouse Rock, Bierce, years later, fondly recalled the "crimson glories of the setting sun fringing its outlines,

illuminating its western walls like the glow of Mammon's fires for the witches' revel in the Hartz, and flunk like banners from its crest." Longing for the pure, powerful wonder he felt when looking upon the landmark, Bierce added "I wish that anything in the heavens, on the earth, or in the waters under the earth would give me such an emotion as I experienced in the shadow of that 'great rock in a weary land.'" The western frontier impressed Bierce as a land of vast expanses, freedom incarnate. As that frontier shrank under the encroachment of westward expansion, Bierce grew ever more resentful of his fellow Americans.

In the first leg, Hazen's expedition met with little trouble as it turned north onto the Old Bozeman trail. The party did bear witness to macabre signposts, however: makeshift grave markers and bone piles, "not always those of animals," pointed the way.

Arriving at Fort Reno on August 10, Bierce, Hazen, and company narrowly missed a string of Sioux attacks in the following days. Regardless, Hazen sallied forth with his meager band heading 67 miles northwest to

Fort Phil Kearny.

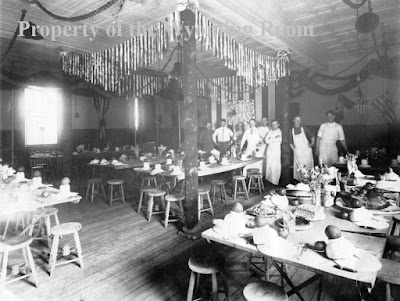

|

Fort Phil Kearny today, a tiny fragment of the structure that stood before

Ambrose Bierce in 1866. The military abandoned the fort in 1868, turning

it over to the Cheynne, who burned down all but a corner of the wall.

Photo property of the Wyoming Room. Click to enlarge. |

The Hazen expedition arrived at Fort Phil Kearny on August 27th and were "hospitably entertained" by the C.O. and other officers. Bierce missed meeting Captain William Fetterman, who fought in many of the same Civil War battles as the future author. In just a few months, Fetterman and others would meet their demise when the Lakota chief, Red Cloud, drew out the fort's soldiers into a massacre.

Setting out from Fort Kearny, the expedition was accompanied by a cavalry detail led by legendary mountain man and adopted Crow chief, 77-year-old Jim Beckwourth. Beckwourth served as a scout for the fort at that time.

Deep in native country, Bierce felt constantly on edge, fearing an attack at any moment. He vividly describes the atmosphere of night on the open prairie: "...turn your back to the fire and walk a little way and you shall see the serrated summitline [sic] of snow-capped mountains, ghastly cold in the moonlight. They are in all directions; everywhere, they efface the great gold stars near the horizon, leaving the little green ones of the mid-heaven trembling viciously, as bleak as steel." In the passage above, perhaps we're seeing what could be described as the stirrings of cosmic dread, an aesthetic common to works of

Weird fiction that Bierce's supernatural horror stories influenced. Appropriately, Bierce punctuates his description of that feeling of helplessness in the face of a bleak, apathetic nature by recounting the eerie echoes of wolves howling and subsequent, nervous glances toward weapons and horses.

At that moment, General Hazen turned to Beckwourth and asked, "What would you do, Jim, if we were surrounded by Indians?" The seasoned mountain man replied, "I'd spit on that fire."

Hazen, Bierce and company arrived at Fort C.F. Smith safely, perhaps awed they made it all that way with their lives. However, there was another danger lying in wait at the fort.

As a teamster lay "dreaming of home with his long fair hair commingled with the toothsome grass," a grazing bison "half-scalped" the man, lifting him in the air by his fair locks. The teamster hollered a few choice words that "were neither wise nor sweet, but they made such a profound impression on the herd, which, arching its multitude of tails, absented itself to pastures new like an army with banners." Thankfully, this was the last hairy situation the expedition encountered.

The expedition set out from Fort C.F. Smith on its way to Fort Benton. On the way, the men swam the Yellowstone and beheld herds of elk and other wildlife more bountiful and varied than their wildest imaginings. Heading in to Benton as a "sorry-looking lot," the expedition got word it was to return to Washington via Utah, Nevada, California, and Panama--what Bierce derided as "a masterstroke of military humour." When Hazen and company passed through California, they camped on the very spot of the Donner Party's fated winter. Bierce, true to his ghoulish sensibilities, felt he must make comparisons about the meat sizzling over their campfire.

Indirectly, Bierce's time in the plains and Rocky Mountains turned him toward his career as a journalist and author. When in California, Bierce got some news. Previously, he had applied for a return to the military, expecting a captaincy. However, to his and Hazen's cantankerous astonishment, the rank offered was a mere second lieutenant. The incensed Bierce wrote back, declining the offer. Later reflecting upon this turning point in his life, Bierce supposed all turned out for the best: had he become a captain in the military, he suspected he would've eventually been killed or become a dotard.

In Sacramento, Bierce worked as a guard during the day and would pore over books from the library at night, giving himself the education he needed and desired. He would go on to write for William Randolph Hearst's newspaper, composing reams of reviews, opinion pieces, and diatribes; fail at both poetry and gold mining in the Black Hills, divorce after seeing two of his three children die before their mid-twenties, wage a personal war against the railroad, champion underdogs wherever he found them, and finally, meet a mysterious end God knows where and when--among many other mis/adventures.

Of the vibrant life and work of one of America's least appreciated and influential authors, it is a small handful of his prolific output that survives in the American mind today.

Yet without the various sources of wonder and horror in his life, we wouldn't have hidden gems like his treasure trove of biting wit and stories so far ahead of their time in their technique and delivery (not to mention their often disorienting or graphic content).

Of Bierce's wit, much of his journalism exists in the 12 (yes, count'em, 12!) volumes of his Collected Works and more famously, his Devil's Dictionary, a collection of reworded definitions aimed at the hypocrisies of America's Gilded Age. Every reader is almost guaranteed to find something to delight and offend in equal measure. Try these on for size:

Conservative, n., A statesman who is enamored of existing evils, as distinguished from the Liberal, who wishes to replace them with others.

Apologize, v.t., To lay the foundation for future offence.

Love n., A temporary insanity, curable by marriage.

And hundreds more, absolutely.

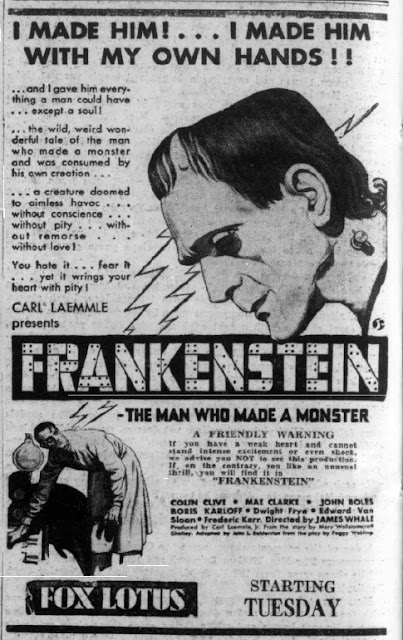

|

Bierce's pen was a deadly--and often persuasive--weapon.

Picture from Edward M. Erdelac's blog. Click to enlarge. |

Beyond Bierce's reams of scathing satire and skewering diatribes, his stories influenced American literature, history, and even 20th-21st Century pop culture. His stories have found their way into the original Twilight Zone, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and recently, HBO's Masters of Horror ("The Damned Thing"). A handful of short films have also been based on Bierce's stories.

Considering the tall tales, war stories, and supernatural horror and Weird fiction he produced, Ambrose Gwinnett Beirce's own tale came to a probably tragic and fittingly enigmatic end. In 1913, at age 71, he left for Mexico. His exact motives, as stated in letters, were vague. Some speculated he wanted to cover Pancho Villa's revolution; others claimed he wanted to fight in it, desiring death on the battlefield--on his own terms. Still others speculate that Mr. Bierce is still with us, having discovered the fabled Fountain of Youth. The Paris Review presents an

interesting variety of theories on the author's fate, with tongue firmly planted in cheek, of course.

The mystery of Ambrose Bierce even made its way onto the silver screen. The 1989 film,

Old Gringo, based on Carlos Fuentes' novel of the same name, featured Gregory Peck as Bierce, providing dramatic speculation on the author's fate.

|

Bierce in his later years. Picture from Time.

Click to enlarge. |

Bierce's final correspondence took the form of a letter to his niece dated December 26, 1913. He appeared to have regained his former vigor, writing "Civilization be dinged! -- It is the mountains and desert for me." His fate remains one of the enduring mysteries in American history. Perhaps 'the wickedest man in San Francisco' proved too much for this weary old world. One could easily imagine him living well past 100 purely out of spite.

The

Sheridan County Fulmer Library has the following books by or about Ambrose Bierce:

Ambrose Bierce: Alone in Bad Company, by Roy Morris Jr.

Ambrose Bierce's Civil War by William McCann

The Devil's Dictionary

The Sardonic Humour of Ambrose Bierce, edited by George Barkin