There is much more to tell, however. With our previous work as an overview, we now present to you some depth of Moore's story as she told it.

My faults are all large and practical: my virtue small, but well selected. Even my severest critics have never been able to deny I have a kind face.

Born on an "old time cattle ranch" near Lake DeSmet on January 1st, 1900, the future writer grew up riding horses, "fixing fence, killing rattle snakes...all part of my charm."

Moore began writing and publishing when she was in elementary school. To 21st Century readers, such precocious literary endeavors sound like they had roots in a passion for the craft; in an interview with Hope Ridings Miller, Moore clarified, "I was virtually coerced, by my relatives, to select writing as my career. Eventually, I got used to the idea." Look at her writing and interviews, you see a subtle, droll sense of humor emerge. Perhaps this was Moore being playful? Whether she was "virtually coerced" into her career, it was an interesting one colored with travel and adventure. We certainly hope she loved every minute of it.

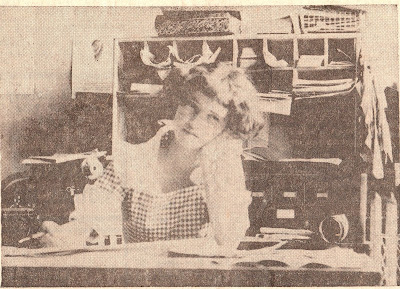

|

| Moore as a young girl, perhaps trying to untangle the plot in one of her stories. From the March 16, 1968 edition of the Sheridan Press. Click to enlarge. |

At Sheridan High School, Moore turned to drama, debate, and public speaking, activities that no doubt helped hone her abilities as a writer--and to no one's surprise, she also worked on the school paper, the Ocksheperida. At the University of Wyoming, she majored in English, probably to no one's surprise.

An exemplary student, Moore wrote for the Sheridan Enterprise (what would become the Sheridan Press) on summer breaks, penning advice to lovelorn Sheridanites as Mrs. Nora Winship. Moore explained that her nom de plume came about because her "baby face did not inspire confidence in [her] worldly wisdom." That is, nobody was allowed to meet her until one Saturday night, where an especially frustrated cowpuncher "broke through the palace guard and came into the city room." Said cowpuncher had been with a widow but was afraid she was "two-timin'" him.

Moore shouted, "Give her up! She obviously is not interested." This had little effect upon the lovelorn cowboy: "But she has four thousand acres!"

Moore continued to write for the Enterprise, branching out to cover everything from "distinguished visitors" to city hall to sports. Of a wrestling match, Moore said "I fell in love with the loser and made him the hero of my story."

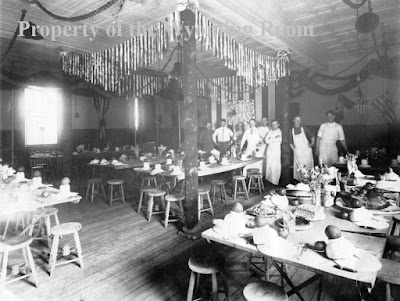

Covering various conventions, Moore implied the "seas of creamed chicken and mountains of combination salad" nearly swept her away. Quite possibly, there can be too much of a good thing.

The Delta Delta Delta sorority alum went on to even bigger and better things. After a stint writing for the Denver Post and a brief return to Wyoming to help her father canvass for governor Nellie Taylor Ross's reelection, she ended up back east first in Cambridge then Washington, writing for the Information Agency and "even a brief spell [as a] press agent for a motion picture.

During Christmastime in 1927, she married Carl Dean Arnold, whom she described as a "nice sort of bloke." Sadly, they were married only 13 years when Dean (who was an actual dean) died at the age of 46.

Shortly after her husband's death, Moore, who would keep her married name, "took a job with a food company" and lobbied "against the olomargarine tax and tour[ed] the country to interview legislators, editors, and organizations." With the onset of World War II, Mrs. Arnold worked for the Office of War Information.

The OWI sent Arnold to London, where she worked for the SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force), then the Allied Press Operation.

Sounds like things got a little hairy on her overseas journey: "Our convoy was fired on by submarines just off the coast of Ireland, but we landed safely." Facing her fair share of close scrapes and less-than-ideal situations, Arnold cherished the experience: "I loved London in spite of the black-outs, the heatless houses and the rationed food, the bomb pits, the ruins."

So she was an adrenaline junkie then? Not at all, by all available accounts. It was Londoners themselves, as she explained, that she admired, "The people were so brave, meeting danger with poise and wit!"

After the war, Arnold went to work for the Information Agency, which she called "very challenging work." She interviewed "officers who returne[ed] from such exciting centers as Santo Domingo, the Congo, and Saigon."

Arnold continued her colorful career with America Illustrated, which partnered with publications in the Soviet Union in an effort to humanize each other's citizens during the Cold War. Arnold covered "success stories of little known Americans, customs, and traditions," preparing her articles for translation. She recounted one humorous translation blunder (anyone in international communication can share hundreds) in which she wrote about American train customs, referring to the smoking car, implying that the Russian translators took the term 'smoking car' literally, since there was no such term in Russian.

Sometime between graduating from UW and the aftermath of the war, Arnold was able to publish an array of short stories and articles, and two novels, Wind Swept and Meet Me in the Lobby. In her interview with Miller, she passed down some humble and sage words for up-and-coming writers. Discounting the usual nonsense about genius or latent talent, Moore stated simply that what successes she enjoyed as a writer came from "persistent effort...[the] tenacity of purpose and hard work." Hard work, yes. Persistence, yes. There was a time when her stories came back, rejected, with astonishing regularity. She wasn't much for arbitrary rules or 'slanting' to the latest market, either. She wrote for the pure joy of sharing what she had to say with the world.

Every author is eventually met with this perennial question: How do you come up with your ideas? For Mary Olga Moore Arnold, it involved dishes. That's right, dishes: "I like to write stories, especially by doing so I can get out of washing the breakfast dishes. I think my best plots when disgruntled dishes are stacked in the kitchen sink."

|

| Undated photo of Olga Moore Arnold. From the Nov.-Dec. 1960 issue of Wyoming Alum News. Click to enlarge. |

Arnold built her stories from her own experience and observations, preferring to rely on her own and nobody else's filters. She usually kept themes lean and clean, though, occasionally, she would light that dimmed candle that kept her alive and writing during World War II, working against" all the rules most editors observe." On one such story, she defied the advice of one of her "best critics"; the Saturday Evening Post published the piece.

To say Olga Moore Arnold's career was not static is an understatement. Fortunately, we have some of her writing at the Sheridan Fulmer Public Library and the Wyoming Room for your enjoyment.